How does someone like Richard McLaren, the law professor and investigator behind “The McLaren Report”—about widespread state-sponsored doping in Russia—follow up on that success?

In this case, it’s by writing a report that is even more unbelievable. But where McLaren’s Russian investigation featured a cast of coolly efficient—if unscrupulous—characters who could have been pulled directly from a Cold War spy novel, his latest effort instead shows a bungling cast of alleged criminals whose brazenness makes someone like Donald Trump look tactful by comparison.

I’m talking about his report on the International Weightlifting Federation, and specifically former IWF President Dr. Tamás Aján.

Ostensibly, the report is an investigation into the IWF, and is therefore a true account of wrongdoings; but the crimes listed are so bold, and the story so beyond belief, that I can only assume Richard McLaren is having a laugh, and that he chose to write a novel.

Hence, I review McLaren’s work as fiction, since the alternative is to confront the indisputably enormous amount of evidence that Aján and pretty much everyone in the IWF was either tacitly or explicitly cool with 40+ years of shocking corruption… (19) [NB: numbers in parentheses refer to page numbers in the report; numbers with “n” indicate a page number with a footnote.]

The story begins in medias res—scandal has erupted within the weightlifting world due to salacious revelations in a German documentary film called “Der Herr de Heber” (“The Lord of the Lifters”). The documentary provides a laundry list of allegations against the International Weightlifting Federation, including financial irregularities, questionable doping control practices, and “kinderdoping,” which might sound like a Dianabol-laced chocolate bar but is actually the use of performance enhancing drugs in children.

It is via this framing device that we meet the book’s hero, or anti-hero, really: Dr. Tamás Aján.

Dr. Aján is a character so fundamentally antithetical to a “hero” that were he to touch a real hero the two of them would likely disappear in a powerful burst of energy, as when matter and antimatter collide.

The entire story is a sort of bildungsroman of this Dr. Aján, a Hungarian physical education teacher and lawyer who, through a series of increasingly improbable maneuvers, ends up not just as President of the IWF, but—in the words of the novel—as a man who “ran the IWF as if it was his own personal fiefdom or private company over which he had absolute control.” (30)

Dr. Aján starts as a plucky young upstart beginning his term as General Secretary of the IWF in 1975. But rather than have Aján slowly work his way to the top McLaren instead decides to have Aján wrestle power as early as 1982 (!), when he inexplicably moves the IWF headquarters from Austria to his home city of Budapest—despite the IWF President being Austrian. (28)

What is his authority to do this? It’s never clarified, although Aján never seems too troubled with things like the IWF Constitution, which McLaren calls largely “a façade of proper legal structure and operating rules.” (27)

It is in those decades prior to his eventual election as IWF president in 2000 that Aján “developed his management style and assertion of total control over all the affairs of the IWF.” (28) The USSR and then the former Soviet Republics are the backdrop against which he amasses more and more control.

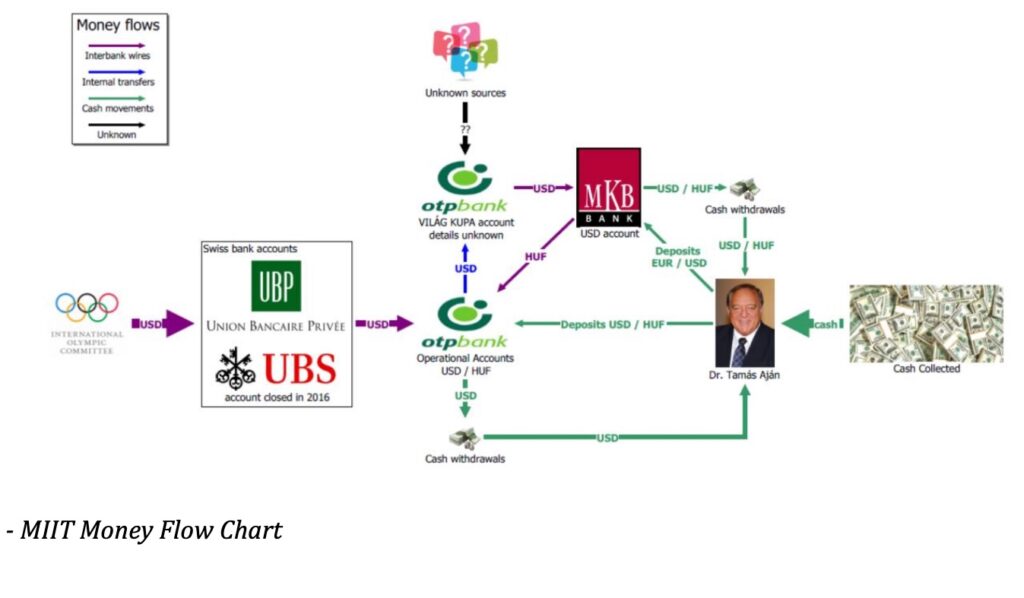

Although this part of the story is not nearly as developed as later decades we do get glimpses of Aján’s growing power: the increasingly lucrative television revenues of the early 1990s, for example, as well as the International Olympic Committee funds, provide the money for the “tyranny of cash” (4) that defines his leadership style.

We also see some hints of how far his reach was in those years: in one scene from 1997, for example, he writes the dates of three upcoming out-of-competition doping tests on a napkin for the Greek Weightlifting Federation’s President, like some mafioso running a numbers game in a NYC Italian restaurant. (91 n37)

Those early decades are sketchy. By the time the story is in full swing—the period from 2009-2019—is when the plot really begins to strain credulity.

While none of the actions in and of themselves are beyond belief—vote buying, embezzlement, theft, and bribery are all routine actions in the international sports world—it is the manner in which they’re carried out that defies belief. Our characters begin to act like caricatures of criminals; all that’s left is to envision Dr. Aján twirling a mustache and cackling maniacally.

Consider one of the more absurd plot twists: we discover, in one scene, that the vote broker tasked with handing out cash bribes (this done via a literal “bag of cash,” like a high school play about the mob) was none other than the IWF’s own 1st Vice President! (87)

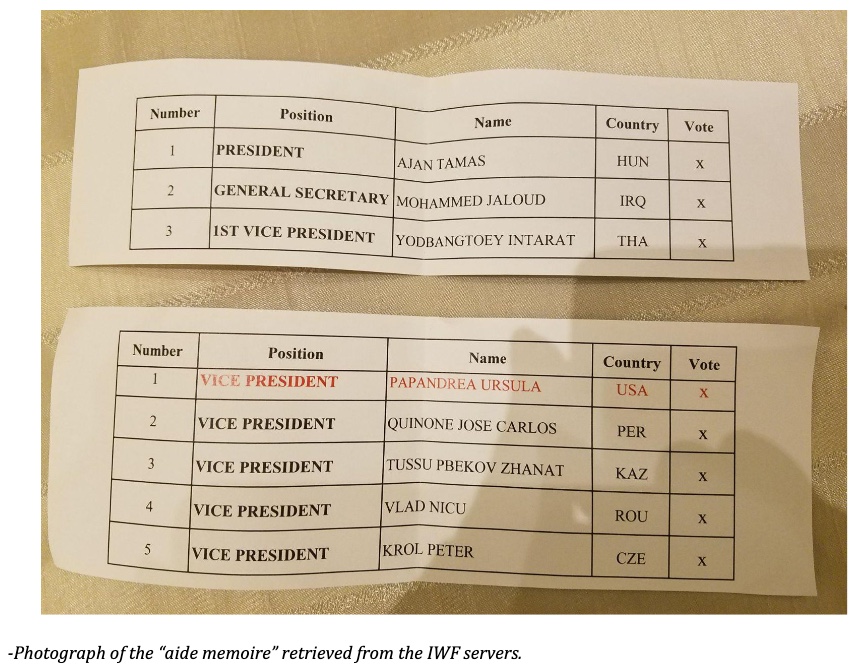

In another scene, the author has Aján and his cronies send out “aide memoires”—literally, pictures of what the completed ballot should look like—to the voting members. (83)

What’s more, the bribed voters then had to send back photographs of their completed ballots as proof of their compliance! (86) If this image—of heads of federations photographing ballots bought with wads of cash—isn’t ludicrous enough to imagine, the author even provides a photograph to illustrate the scene.

McLaren also peppers his story with lines that seem taken out of the first draft of a gangster screenplay; consider the following, allegedly spoken by the Ugandan Weightlifting Federation’s President when he discovers that the cash had run out and he’d have to come back for his bribe: “I want my money now. I’ve voted for you.” (87 n36)

Or when the IWF auditors arrive to look at the financial records and Aján allegedly responds by gifting $100 or a bottle of whiskey and saying, “Here you are, here are the books. Sign them and we go to dinner.” (44).

As the story develops it groans under the cumulative weight of so much criminal and unethical behavior. Aján creates a position within the IWF, has it rubber-stamped by the Executive Board, and then fills it with his son-in-law (35); he exploits board members’ poor knowledge of English to get them to vote against their own interests (37 n10); he threatens countries with doping tampering (37; 41); he opens several secret bank accounts and fills them with IWF cash (some $10.4 million, just in the book’s main decade). (53-55, and pretty much all of chapter 3)

McLaren’s writing is breezy, and cuts to the heart of the matter. The book can be a real joy to read at times, peppered with phrases like “the presidential and other elections that took place during the period from 2009-2017 were astonishingly bribery prone,” (77) as if bribery were something you might catch if you forgot to wear a coat outside in the winter.

It conjures an image of anthropomorphic elections walking around and coughing and saying things like, “Sorry, I’ve just come down with a small case of bribery. Nothing serious.”

As fun as this book is to read—the 122 pages disappear almost as quickly as the IWF’s financial records (57-58; maybe they were “destruction prone?”)—it is ultimately too unbelievable for its own good.

In addition, Aján, despite being our central character, has no growth or arc. Even in the face of potential threats he never fails to act with reckless disregard for propriety: to give just one example, when the Internal Auditors Committee raises allegations of financial irregularities in 2009, Aján responds by (1) disbanding the committee, (2) replacing them with external auditors, and (3) personally hiring and selecting those auditors. (45) Plus ça change…

He starts the book as a corrupt, power-hungry bully—e.g., “[leveraging] the rumours and stories of his doping manipulations to instill a sense of fear of what could happen if Member Federations challenged his authority” (91, emphasis in original)—and that’s exactly how we find him at the end, refusing to take his hands off the IWF reins even when he is supposed to have stepped down. (15)

Despite the far-fetched nature of this book, it has already spawned its own branch of fan fiction—some of which is just as absurd as the original work. The fanfic short story “Tamas Ajan: Claims in McLaren Report ‘Unfounded’” imagines the former president still protesting his innocence, despite an almost comical pile of evidence that suggests otherwise.

Another story, “Current IWF Board should not decide on weightlifting’s future, says Canadian ousted by Aján vote-buying,” tells the story of the IWF Executive Board claiming—without a hint of irony—that they can handle the cleaning up of the IWF—despite allegations of several of them having been elected via bribes.

And a current Executive Board member was the vote broker who allegedly paid the bribes! (87) If there ever was a case of the fox asking to guard the henhouse this is it; recall that in McLaren’s tale the Executive Board was cool with “business as usual” until an outsider—the German doc team—forced them to act.

One of the few characters who makes any sense in this response to McLaren’s tale is Moira Lassen, who was voted off the IWF board in one of the (several) rigged elections.

She says, “An entirely independent group should come in to run the IWF from now until the next elections, and those elections must be very closely monitored.”

One would assume this is so patently obvious that the rest of the story would mostly be about agreeing on the matter and moving forward with it.

Instead, Board members continue to argue they can best handle the matter—a tactic drawn from the very President whose actions prompted this investigation! [NB: I suppose it’s possible that some of this fanfic is meant as satire; if so, I retract these criticisms].

That said, Richard McLaren’s “Independent Investigator Report to The Oversight and Integrity Commission of International Weightlifting Federation” is still a rollicking good read, for all its flaws.

Like David Foster Wallace’s “Infinite Jest” it portrays a world that, on the surface, seems beyond belief—but which may be closer to reality than we’re comfortable admitting.

4/5 stars.

[NB: If only the McLaren report were satire; sadly, it is not. According to McLaren’s findings, Aján actually was this ethically reprehensible, all with the tacit or explicit support of the people around him. Everything in this essay is drawn from McLaren’s findings. As is so often the case, men in power (it was nearly exclusively men) exploited people below them for their own personal gain; in this instance, hundreds if not thousands of athletes were literally nothing more than an afterthought to the steady stream of cash that lined the pockets of Aján and his cronies.]

Enjoyed the book review. I had a few chuckles but then was in deep silence.